“If fighting for equal pay and paid family leave is playing the gender card, then deal me in!” ~ Hillary Clinton

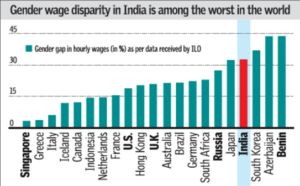

Emancipation movements across the globe have opened the doors of schools, employers and boardrooms to women. Yet in India, despite the relatively lower male-female sex ratios, women continue to face gender discrimination when it comes to the payscale. The Global Wage Report released by the International Labour Organisation in 2016-17 (ILO Report) shows that in India, cultural barriers, occupational segregation (giving preference to male workers while training, recruiting or promoting to senior roles), and role stereotyping (childcare, cooking etc. being viewed primarily as women’s domain) considerably weaken women’s bargaining power vis-à-vis wage parity.

The ILO Report notes that the payscale gap in India exceeds 30%, and that Indian women comprise 60% of the lowest paid wage labourers, but only 15% of the highest wage-earners. Even in the more highly paid sectors, such as private law practice, the Monster Salary Index of 2016 (MSI) reports that the gender pay gap in law firms is about 27.5% per hour. All of these statistics do not bode well for the egalitarian ethos that is prized in India so much.

The idea that men and women receive equal pay for similar work done by them, is grounded in the norms of equality before law and prohibition of unreasonable discrimination as enshrined in Article 14 of the Indian Constitution, which is the “basic structure” of the Indian Constitution. The same principles have been embodied in the (Indian) Equal Remuneration Act, 1976, which aims at preventing gender discrimination with respect to recruitment, wages, employment policies, work-transfers and promotions across all industries and sectors, whether organized or unorganized. Admittedly, the Equal Remuneration Act does not cover self-employed female workers in sectors such as farming and household businesses. However, the judiciary too has stepped in to assuage any statutory deficiencies declaring that while the “equal pay for equal work” is presently not a universal right, it is certainly a laudable constitutional goal to be upheld. In Randhir Singh v. Union of India, the Supreme Court recognized the right to equal pay for equal work as part of Article 14 of the Constitution, and observed that in cases where all “relevant considerations are the same”, the Government of India could not deny equal pay to women, directly or indirectly.

Given the legislative, judicial and constitutional acknowledgement of the “equal pay for equal work” principle, there are enough guidelines and incentives for administrative and business institutions to build capacity and infrastructure for wage parity. On the other hand, the deterrent effects of these guidelines often get subverted by organizations which either treat women as dispensable staff who may be maneuvered into less lucrative departments or designations. The need of the hour is, therefore, a more stringent legal framework that also requires due disclosures from employers on its wage platforms, changes in its employment structures and its human resources policies for ensuring equal employment opportunities and prohibiting gender discrimination at the workplace.

Fair and equal treatment of all workers is of the greatest significance. It is, no doubt, a politically sensitive issue centred on natural justice and basic human rights, but is also a matter which affects the productivity and sustainability of the labour force. By ensuring “equal pay for equal work”, we demonstrate to Indian women how much we appreciate their industriousness, more than just on April 10.

Picture Credits: thehindu.com , cnn.com

Please note: The views, opinions and beliefs expressed by the authors in the articles on the blog are theirs alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Lean In India.